Tokenomics Vol. 1

Tokens, FDV, and Supply

It’s more than just a casual DYOR (do your own research). Understanding the economics behind a token is a critical step in understanding any potential crypto investment. This is the first post of a series on Tokenomics.

Background: What are tokens?

Many types of crypto assets exist. The term “crypto assets” generally refers to digital coins or tokens that represent something in a crypto ecosystem.

Tokens live on blockchains, but they are separate from coins. There is only one coin per blockchain. For example, Ether is the coin to transact on the Ethereum protocol. Tokens represent smart contracts.

Each token, via its contract, establishes a standard or represents the value of an action or incentive. Aave, which we mentioned in our recent post on DeFi, is a token on the Ethereum blockchain that allows its holder to govern the Aave protocol.

Payment tokens, governance tokens, or utility tokens each have different use cases. Some tokens are used to raise capital (which could be illegal securities), some are used to drive adoption of an application ($BAT), and some are used as means of payment for a service in an ecosystem ($HNT).

Before launching a token, blockchain developers must make decisions that determine how the token will exist. Questions like:

What is the total supply of the token?

How might that supply change over time?

What smart contract platform will the token exist on (ie: choosing Ethereum or Solana)?

Will owners have the opportunity to stake assets to earn rewards?

There are dozens more questions to consider, which makes it easier to understand why thousands of tokens exist with various properties, supplies, and mechanisms. Crypto is largely in the phase of experimentation with these models to see what has long term viability.

But they all have tokenomics.

Tokenomics

Tokenomics refers to the economics of a token. At its simplest form, it is the supply and demand for the token, with assorted buyers and sellers.

But the term is more nuanced. By understanding current and future supply levels, you can predict the market’s price reaction in advance. For example, when token unlocks occur and more supply floods the market, how will the market react?

At the end of the day, tokenomics is a game of incentive design, to incentivize particular actions or ownership. Many times, the tokenomics are designed such that the token price should go up over time due to supply side drivers: Bitcoin’s supply cap and decreasing inflation being one example.

In this first piece on tokenomics, we will explore the supply side of tokens, including some terms: fully diluted value, and token quantity. Subsequent posts will dive into token allocations, emissions, demand and utility, and evaluation strategies.

Terms

These are important terms to understand before making a dive into tokenomics.

Circulating supply - How many tokens are in the market right now?

Total Supply - How many tokens were created on-chain but locked, released to market, and/or burned?

Max supply - How many tokens will ever exist?

Market Cap - token price multiplied by the circulating supply

Fully Diluted Value (FDV) - the token price multiplied by the max supply.

Inflationary - token supply is increasing. A token will decrease in value if more of them exist over time.

Deflationary - token supply is decreasing. A token will increase in value if fewer of the tokens exist over time.

MC/FDV - measure of inflation, a ratio of how much future supply must be absorbed by the market.

Distribution schedule - How quickly are new tokens being released? How will the available supply change over time?

Unlock (Emissions) schedule - Who owns most of the supply? When can they sell?

Supply Strategy - Is the supply unchangeable, or is a formula that determines supply unchangeable?

Key points from the terms above:

Tokens are either inflationary or deflationary.

Tokens have a fixed max supply or an infinite max supply.

MC/FDV is a key metric to understand supply. A ratio closer to 1 signifies low future inflation. Closer to 0 leads to significant supply inflation and sell-side pressure. This matters because tokens can increase supply quickly and unexpectedly without increasing demand. Tokens with ratios closer to 0 have a tendency to dilute in value over time if they don’t achieve significant adoption.

We can look at examples to understand the basics of the supply side of tokens.

Examples

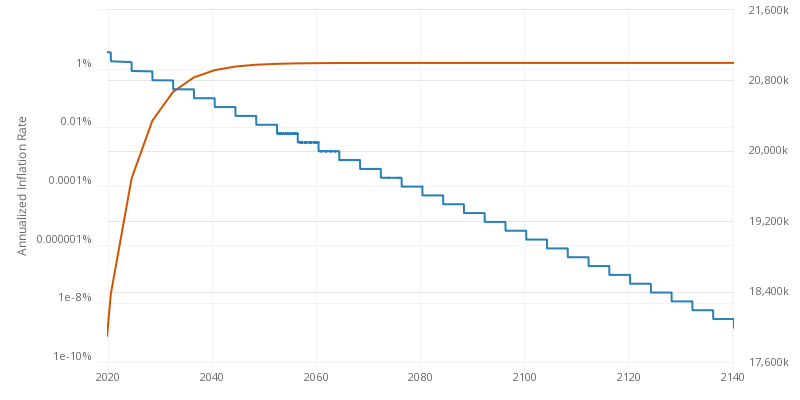

Bitcoin - inflationary with a supply cap

The supply of bitcoin is capped at 21,000,000 bitcoin. Nobody can change that, ever. The release rate gets programmatically cut in half approximately every four years. Currently the MC/FDC ratio is $460B/$506B, or 91%.

Ethereum - inflationary with no supply cap

Ethereum has no max supply. There are currently 121M tokens in circulation. The supply dynamics of ETH are set to change after The Merge in September.

Binance - deflationary with a supply cap

The BNB token has 161M tokens in circulation. The max supply is 200M. However, Binance plans to reduce the supply to 100M, meaning that the MC/FDV is 81% but the supply will decrease by 31% over time.

Flow - inflationary with no supply cap

The FLOW token currently has 1.04B tokens in circulation. There are also 200M tokens still locked. There is no maximum supply. We will continue to look at FLOW tokenomics in subsequent posts.

Now you have a grasp on the basics of the supply side of tokens, including inflation, fully diluted value, and token caps.

In subsequent posts, we will dive into mechanisms around token release, initial token allocations, emissions, demand and utility, and evaluation strategies.

These posts will answer questions like: why is token value so volatile? why does the circulating supply change so much? how are tokens designed to add value? and more.

Resources

What goes into creating a token?

What is a crypto token?

Market cap and FDV